I really should kick this off with a big disclaimer: I’m a book guy.

I grew up in a book house—my dad is a professor and the author of several books, and my mom worked in a library when I was a kid. Bibliophilia is in my genes—my toddler already goes straight to her books immediately on waking up. I love places where books live—I’ve haunted libraries, bookstores, and free book spots in every town I’ve ever lived in. I read books in multiple languages—I’m literate in German, with passable French and Spanish skills. I even write books—I’ve got several novels in progress, including one story with a finished draft that I completely scrapped instead of sending to an agent because it wasn’t quite there yet.

But recently, I’ve ditched at least 300 volumes from my personal library, some of which I had owned for over 15 years.

If you’re trying to downsize too, read on for 10 tools to help you winnow the chaff from your personal library. But first, a brief aside to answer the why.

Why Get Rid of Books?

Three years ago everything changed forever when my wife and I welcomed our first child into the world. When you’re staring into huge life events—birth, death, changing jobs/graduating/moving across state lines—it’s pretty common to step back, size up the big picture, and measure it up against your desires.

My big shift bore in its saddlebags the realization that I had set up my life to serve the written word, instead of the other way around. I’d spent my teens and twenties filling up private notebooks instead of filling up my life experiences, learning theory instead of gaining practice, consuming instead of creating. I’d been content with peering through a telescope when I had ample opportunity to slip into a space suit and make footprints in moon dust. And because of that lopsided value system, I kept every dadblamed book that ever crossed my path.

As I grasped that I wanted to write not only in books, but also on my heart and in the lives of other people, 80% of my personal library suddenly became clutter. Certain books that were relevant in high school or early college had no bearing on my life anymore because as the earth had completed each rotation around the sun, I had become a different person. As I jettisoned each irrelevant volume, I felt lighter from removing one more ounce of the past from my pack and leaving it on the trail.

But sometimes it wasn’t so clear which books I truly wanted to keep versus which books I was holding onto for unhealthy reasons. Have you ever faced this? If so, I’d like to open up my toolbox and share what helps me.

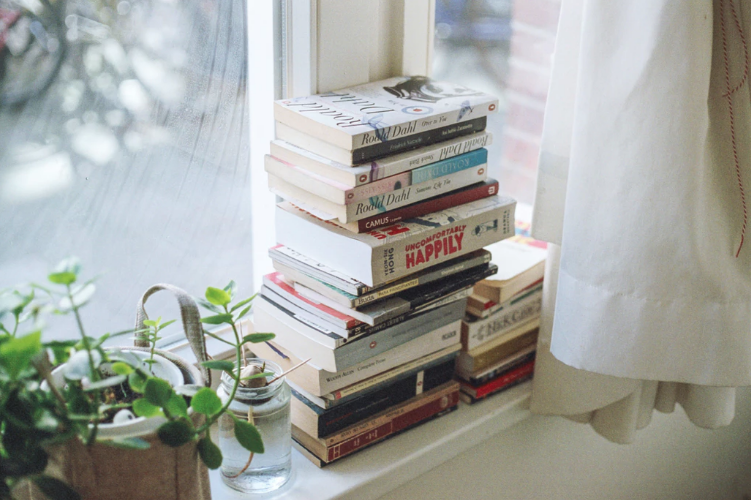

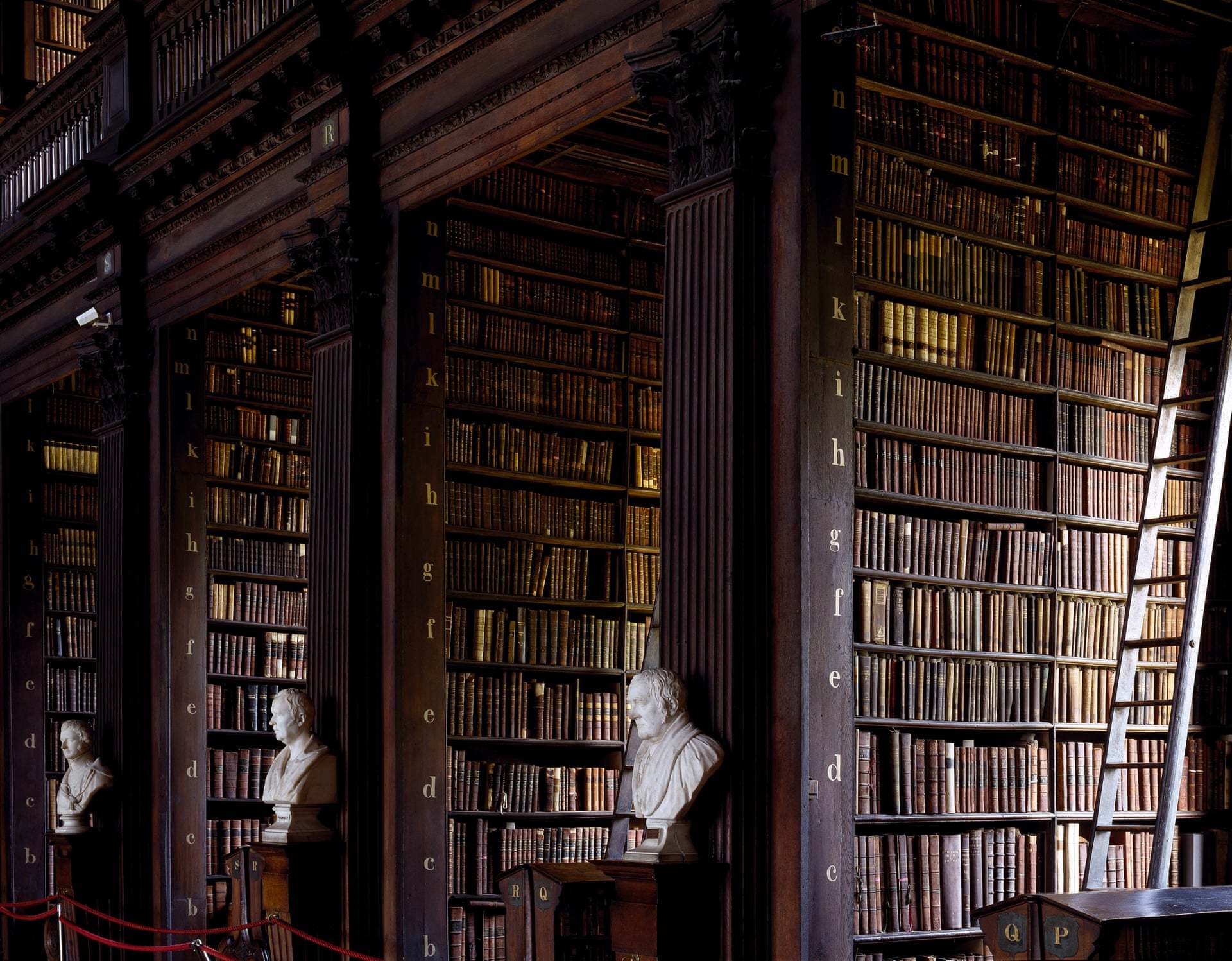

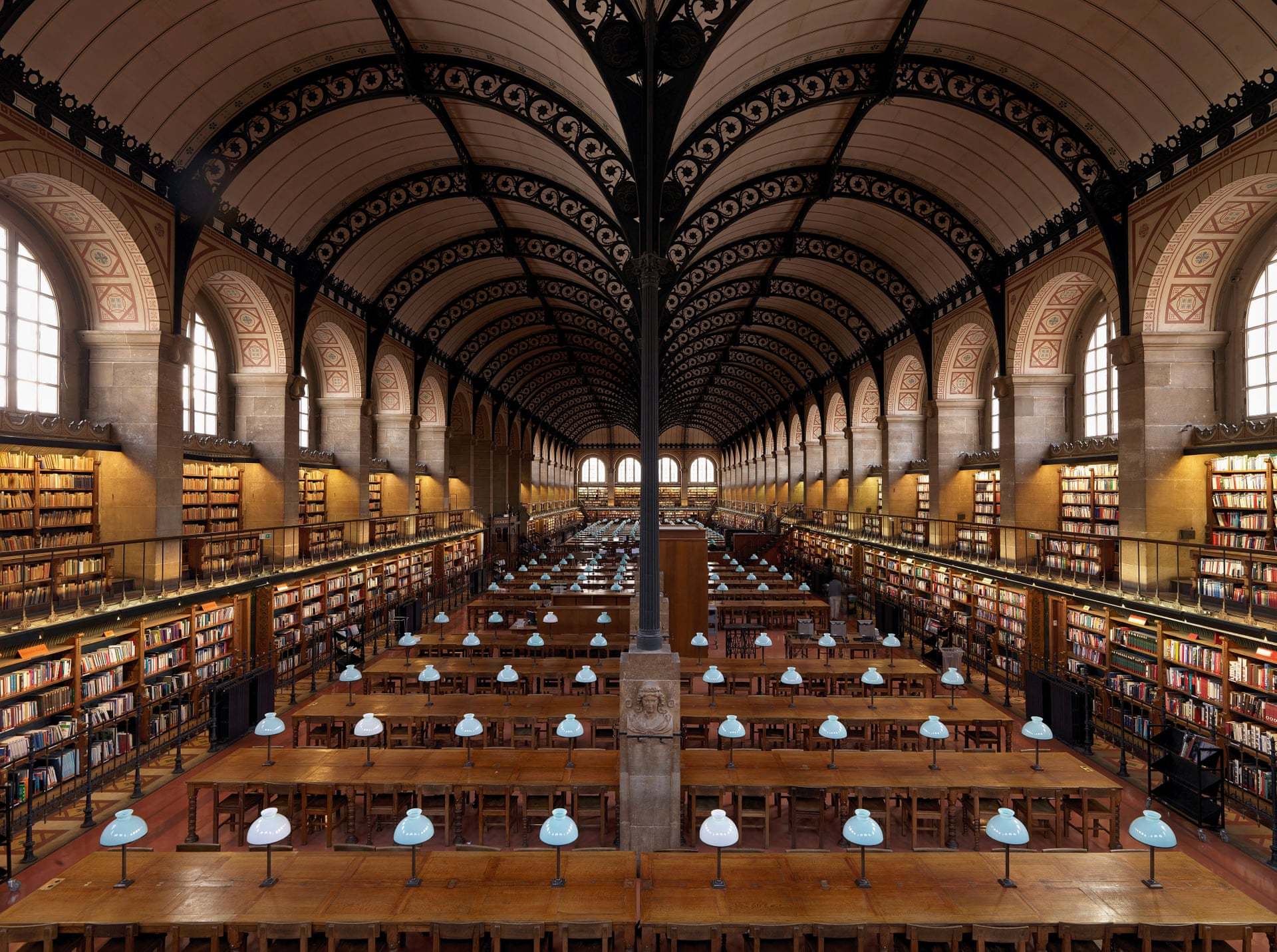

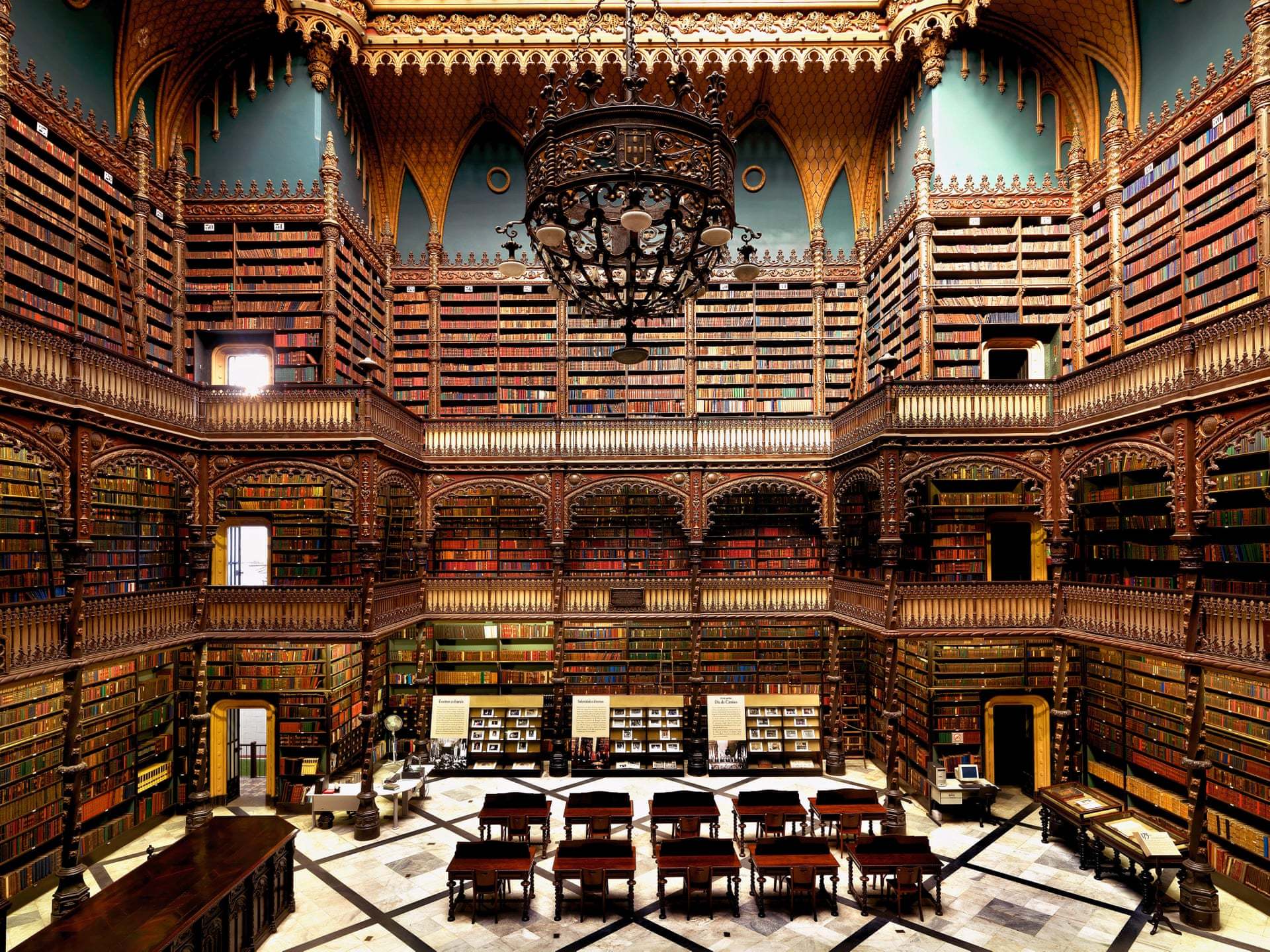

(By the way, I’m going to taunt you during this whole post with photos from the world’s most beautiful libraries.)

1. Build a desert island shelf

We’ve all got those beloved books that we’re going to have to write into a will, because the Grim Reaper’s scythe is the only thing that’ll separate us. Why not give them a physical distinction by designating a specific, finite space for the books you can picture yourself marooned with on a little spit of land in the middle of the ocean with naught but a single coconut palm?

Install an isolated shelf somewhere in your house, or simply clear out a bookcase shelf, and fill it up. Not only is it an interesting thought experiment to determine your absolute favorites, but it’s also a standard of measurement—when you decide which books are essential, you decide which books are not, and therefore you can get rid of them when you need to. For me, the biggest deciding factor in my desert island shelf is not that I simply liked it a lot, but whether or not I’m going to refer to it regularly.

(It’s up to you what size your desert island shelf should be, but bear in mind that if you’re trying to downsize, a single shelf is more effective than an entire bookcase.)

Example: Amid Amidi’s Cartoon Modern is the best and most thorough compilation of Mid-Century animation art, and I constantly reference it in my illustration work. I also unknowingly bought it a year before it went out of print, and now even used copies sell for nearly a hundred bucks. I don’t plan on getting rid of it for quite a long time.

2. Use the internet for most of your research

Now, there are limitations to this tool, but for most of your general research needs, it’s incredibly effective to just Google it. The first-ever public website debuted in 1991 and now there are over a billion. Encyclopedias and dictionaries are online; Google Books allows you to instantly search entire texts of books that would be immensely difficult to find hard copies of. And that doesn’t even begin to touch web user-generated information, which doesn’t pass through quite the same quality control as traditional media, but which you can put to the test yourself.

It’s really hard to justify keeping a 30-volume encyclopedia set for the purpose of general reference. If you’re trying to get rid of books, funnel out your general reference materials and keep only the stuff specific to your interests.

Example: Seed to Seed is fantastic reference book specifically for saving vegetable seeds. It’s an obvious keeper in my garden reference library because I go to it for relevant, trustworthy information exclusively instead of filtering through internet search engine listings.

3. Ditch the duplicates

If you’re an incorrigible bibliophile like me, you’ll admit to owning multiple copies of the same book. It’s outside of the scope of this article to discuss why we do this, but it’s a fact that we do.

You know what, though? Out of all those copies, chances are good that you’ve got a favorite. Do yourself a favor: keep the favorite, give away the others. If you really love that book so much, you’re going to want to share it, right?

Example: I went through a Walt Whitman phase in college, and there was a time when I owned no less than three copies of Leaves of Grass. Seriously? Let him sing the “Song of the Open Road”… on the open road.

4. Follow the 5-year rule

I’m not a particularly efficient reader—maybe it’s ADD, maybe it’s because I give my attention to not only the words’ meaning but also the writer’s style and voice, the way the words’ sounds meld together, and the book’s visual aspects (typefaces, paper color and feel). So when I’m sorting through books for considering which ones to release, I ask myself: have I even thought about this book in five years, let alone consider reading it? If I haven’t gotten around to it but I’m keeping it “just in case,” I try to ditch it. I figure that if I really want to read it one day, I’ll just go out and buy a new copy, and then I’ll really be excited about it. (This has not happened yet.)

Example: I bought a used copy of The Short Stories of Ernest Hemingway at the Royal Oak Book shop in Front Royal, VA in the summer of 2002. I had just finished The Sun Also Rises and discovered the stick-to-your-ribs meat-and-potatoes quality of Hemingway’s prose voice, I read quite a lot of the stories in that paperback volume over the years, and I loved that copy. But about a month ago, I finally gave it away when I realized that I hadn’t cracked it open since 2011 because I just wasn’t that into Hemingway anymore.

5. Catch-and-release, not taxidermy

If you really love books, you’re not going to keep them yourself, you’re going to share the joy. Check your bookshelf: how many of your most beloved books did you buy used? What if their previous owners hadn’t let them back into the wild? When you’ve decided to set a volume free in a catch-and-release program, you get to enjoy the satisfaction of knowing that you’re giving someone else the chance to like a book you liked. (The thing about a taxidermy display is that those animals have to be dead to be stuffed.)

Example: I really enjoyed Hermann Hesse’s Siddhartha in the original German during my foreign exchange year and I thought it would be something my host brother would enjoy, so before I moved back to the States, I gave it to him as a gift. Did he ever read it? No idea, but it made me feel good at the time, and I guarantee I was never going to flip through those pages again.

6. Internalize the book’s big idea

When you’re reading a book for pleasure, it should be easy to give it away once you cross the “The End” threshold. It’s tougher to release a book you’ve read for information, because if you give it away and then forget it all, what was the point of reading it in the first place, right?

Well, how about you just set out to remember one or two things from every book you read? Remember that every book is built around a central premise—English teachers call it the theme, but that sounds too much like school, so I call it the “big idea.”

To help me remember, since 2006 I’ve been keeping a written record of the books I’ve read. I use a specific notebook for this purpose (currently a Moleskine book journal) and I write down the big idea summed up in a sentence or two, one or two actionable ideas if applicable, as well as my personal impression of the book and 1–3 direct quotes that stuck out to me.

Example: One of the first entries in my first book journal is The Ghost Map by Steven Johnson, the retelling of a cholera outbreak in mid-1800’s London and how it changed our understanding of germ theory, which I read in 2006. It follows a doctor who wasn’t buying the prevailing wisdom that people were getting sick from “bad air,” and who eventually traced the outbreak to a single water pump on a street with a source tainted with raw sewage. I remembered all of this without referencing the journal—it’s remarkable how much you can enhance your memory by gathering your thoughts and filtering them onto a page.

7. Don’t buy when you can borrow

Again, please don’t misunderstand me: I love bookstores—independents, big retailers… heck, even buying books online. But I’m also trying to make less library work for myself by stemming the flow of books on my shelves by borrowing from the library, especially when I have a feeling I’m not going to keep the book after reading it.

Example: I love cookbooks, but my culinary library gets out of control really quickly, so I check ’em out from the library before I decide to invest money and bookshelf space. I’ve borrowed Artisan Pizza and Flatbread in Five Minutes a Day from the Lee County Public Library every few months for the past year, so it’s safe to say I need to buy my own copy.

8. Invest in an e-reader

This just in: digital technology allows you to store an entire city block’s worth of information into a slim plastic box!

Physical book lovers, before you run me out of town, hear this. I’m a physical book guy down to my marrow. I love the smell of paper and the look of real ink. I love the sound of pages turning and the creak of a spine. I have a background in graphic design, so I literally judge the covers of books, and a well-typeset volume adds the satisfaction of beauty to my reading experience. I hated the idea of e-readers when they made their way into the hands of first adopters.

But I gotta say, these days I cotton to the idea of filtering some of my reading through a Kindle or Nook because managing physical resources can get tedious and expensive. (Plus, I just discovered that you can change fonts on your e-readers now, so you’re not just stuck with the default Times New Roman.)

Example: I’d like to start reading more classics, which are really easy to find for e-readers, sometimes free, and always way easier to travel with—who really wants to shove a doorstopper like Moby Dick into their carry-on?

9. Rewards: launch a book, buy a book

This is like the anti-deforestation measures of “chop a tree, plant two in its place.” Remember that this isn’t really an article about minimalism, but about getting rid of unnecessary stuff—and if you’re like me, new books are necessary. So when I’m shedding books I don’t need anymore, I remind myself that I’m making space for books that I want—for every several books you get rid of, I have a rule that I get to buy a new one.

Example: I’m a big fan and regular practitioner of haiku, and the best collection of native English haiku I’ve found is the Haiku Anthology, which I’m going to buy now that I’ve cleared out a batch of poetry books that I’d grown disinterested in over the last decade.

10. Don’t rush the process

Finally: remember that this is a no-pressure situation. If you don’t get rid of all of your unwanted books today, A) no one’s going to die, 2) your house isn’t going to spontaneously combust, and D) your left arm isn’t going to become leprous and fall off. If you’re not positive you want to get rid of a book, leave it on your shelf until you’re sure! Remember the Hemingway Stories book? It took me half a decade to finally discard it.

Bonus: recommendations for getting rid of books

Here are some ideas of where to productively send your books once you’re done with them:

1. Donate them:

- Operation Paperback —Nonprofit that sends gently used books to deployed military.

- Books 4 Cause — Nonprofit that diverts unwanted books from landfills to teachers, underprivileged communities, and African libraries.

- Better World Books — Online marketplace for used books that raises funds for charity.

- Little Free Library — I’ve got one of these in a nearby park downtown and I’ve restocked it multiple times.

- Charity thrift shop — You can never go wrong passing along your gently used books to your local Goodwill or Salvation Army.

2. Sell them:

- BookScouter — It’s originally geared toward textbooks, but I’ve had some other nonfiction books price well. The best part is that they provide a free shipping label for when you’re ready to ship off a batch.

- Used bookstore — Check your local bookstore’s buyback program; sometimes they’ll pay more if you opt for store credit.

Add comment